Pain Science Pt. 2 - The Brains Response to Pain

““Healing severe or chronic pain, I believe, includes transforming our relationship to the pain, and, ultimately, it is about transforming our relationship to who we are and to life.” ”

The Body is Designed to Manage Pain - The Science

In the previous article, we had discussed the neurological experience of what happens when we have the sensation of pain. We followed a path from the noxious stimulus, into our sensory cells (nociceptors), up through our spinothalamic tract, and into the three regions of the brain which synergize to create our unique perceptual experience. Luckily, the story doesn’t end there, otherwise we would be overwhelmed from the constant barrage of nociceptive information coming into our central nervous system. In order to tend to the painful stimulation, the brain is equipped with mechanisms which can control and inhibit nociception. If it didn’t have this capacity, we wouldn’t be able to think clearly enough to remove ourselves from potentially dangerous situations. This exploration is dedicated to those mechanisms and how understanding them can be incorporated into our massage practice.

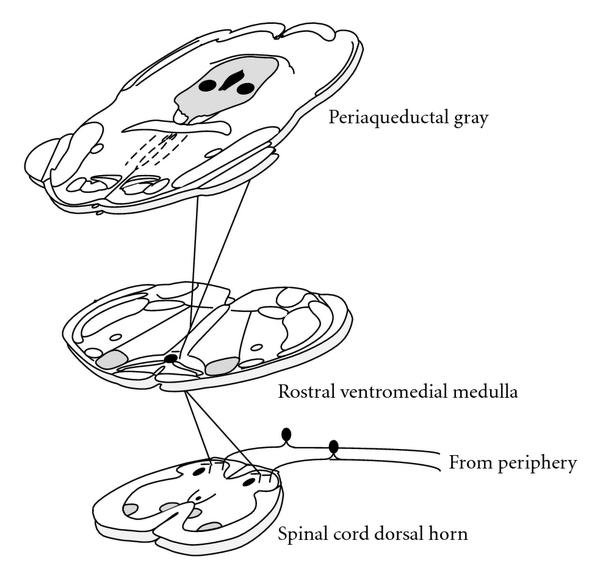

Once the perception of pain is generated in the brain via the higher cortical structures, a top down response is immediately mounted in a process called the ‘Descending Pain Modulatory System’. This process begins in a part of the brain called the periaqueductal gray which is an area of gray matter that is located in the mid-brain. This is the primary center for modulation or propagation of nociceptive information. This means that it can both dampen and heighten nociception. It is also responsible for learning and acting out defensive or aversive behaviors.

In order to do this, it relays the signal from the cortical brain structures into another structure called the nucleus raphe magnus which is located in the Rostral Ventromedial Medulla. When the signal reaches this point, it synapses (crosses between two neurons via the synaptic cleft) with a serotonergic neuron that shoots down both serotonin and noradrenaline (amongst other things) into the dorsal horn of the spinal column. Once these chemicals are released into the substantia gelatinosa (a thin cap of gray matter covering the dorsal horn), they do two things.

1. They bind with the original peripheral nerve which is bringing nociceptive information into the dorsal horn, inhibiting it from transmitting a substance called ‘Substance P’ which acts as the first transmitter of nociception.

2. It also stimulates a small opioid interneuron within the substantia gelatinosa which releases an endogenous opioid called enkephalin, which inhibits the receiving neuron in the dorsal horn from sending the nociception up to the brain.

Dorsal Horn and Substantia Gelatinosa Location - http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/

Gate Control Theory - Where Massage Comes In

To simplify this process, we could say that descending modulation operates by closing a gate in the dorsal horn which prevents an amount of nociception from traveling into the brain. This idea of gating is described by the famous Gate Control Theory that I mentioned in the prior post. Published in 1965 by Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall, this famous theory of pain paved the way for many modern pain management practices. It dovetailed from prior theories of pain management by including our emotional experience as one of the contributors to whether our nerve gates were open or closed. It also provided an easy to understand mechanism for how chronic and phantom limb pain could be possible.

Their postulation was that a disruption in the gating mechanism causes the gates to become “sticky” in that they lose their ability to open and close effectively. When this happens, the persistent hum of nociception we receive on a daily basis doesn’t get dampened and we’re stuck with a constant sense of ache. This is exacerbated by the emotional and psychological landscape we find ourselves in, creating a feedback loop of anxiety and pain. In the absence of tissue damage, our hopes to disrupt this feedback loop is going to come down to how well we can affect the psychological and emotional responses to the experience.

If we are to take this theory to heart, it opens up a range of possibilities in responding to chronic pain. Some of the most readily used methods are,

1. Focusing on something else

2. Relaxing

3. Exercise

4. Staying optimistic/ avoiding catastrophizing

5. Counter stimulation techniques (such as massage, acupuncture, chiropractic)

This reiterates the idea that pain is a bio-psycho-social experience. While there are often biological reasons we are experiencing pain, much of our sensation is created by a confluence of emotions, thoughts, and expectations. This constellation of forces dictates whether or not the gating system in our spinal column is operating succinctly. Massage therapy is a wonderful way to establish a new relationship with our pain and deescalate the anxiety we often feel surrounding it. Through the combination of therapeutic touch, education, and a clear treatment plan which changes and accommodates to the unique needs of each client; we can encourage the nervous system to inhibit some of the nociceptive information it receives.